Ghost City Tragic Soul Symphony Free Download

| Symphony No. 8 | |

|---|---|

| "Symphony of a Thousand" | |

| Choral symphony by Gustav Mahler | |

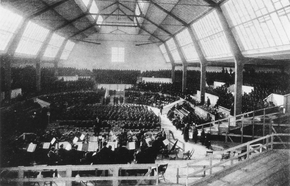

Last rehearsal for the world premiere in the Neue Musik-Festhalle in Munich | |

| Central | E-apartment major |

| Text |

|

| Composed | 1906 (1906) |

| Movements | five |

| Premiere | |

| Date | 12 September 1910 |

| Conductor | Gustav Mahler |

| Performers | Munich Philharmonic |

The Symphony No. viii in E-flat major past Gustav Mahler is 1 of the largest-scale choral works in the classical concert repertoire. As it requires huge instrumental and vocal forces it is frequently called the "Symphony of a Thousand", although the work is ordinarily presented with far fewer than a 1000 performers and the composer did not sanction that name – actually, he disapproved of it.[1] The work was equanimous in a single inspired flare-up at his Maiernigg villa in southern Austria in the summer of 1906. The last of Mahler's works that was premiered in his lifetime, the symphony was a critical and popular success when he conducted the Munich Philharmonic in its first performance, in Munich, on 12 September 1910.

The fusion of vocal and symphony had been a feature of Mahler'southward early works. In his "middle" compositional catamenia after 1901, a change of style led him to produce three purely instrumental symphonies. The 8th, mark the end of the heart period, returns to a combination of orchestra and vox in a symphonic context. The structure of the work is anarchistic: instead of the normal framework of several movements, the slice is in two parts ("1." and "2. Teil"[two]). Part I is based on the Latin text of Veni creator spiritus ("Come up, Creator Spirit"), a ninth-century Christian hymn for Pentecost, and Part Two is a setting of the words from the closing scene of Goethe'southward Faust. The two parts are unified by a mutual idea, that of redemption through the power of love, a unity conveyed through shared musical themes.

Mahler had been convinced from the start of the piece of work's significance; in renouncing the pessimism that had marked much of his music, he offered the 8th as an expression of confidence in the eternal man spirit. In the period following the composer'due south death, performances were insufficiently rare. However, from the mid-20th century onwards the symphony has been heard regularly in concert halls all over the world, and has been recorded many times. While recognising its wide popularity, modern critics have divided opinions on the work; Theodor W. Adorno, Robert Simpson, and Jonathan Carr found its optimism unconvincing, and considered it artistically and musically junior to Mahler'due south other symphonies. Conversely, information technology has been compared by Deryck Cooke to Ludwig van Beethoven's Symphony No. ix equally a defining human statement for its century.

History [edit]

Background [edit]

Past the summer of 1906, Mahler had been director of the Vienna Hofoper for nine years.[due north 1] Throughout this fourth dimension his practise was to leave Vienna at the close of the Hofoper season for a summer retreat, where he could devote himself to limerick. Since 1899 this had been at Maiernigg, near the resort town of Maria Wörth in Carinthia, southern Austria, where Mahler built a villa overlooking the Wörthersee.[4] In these restful surroundings Mahler completed his Symphonies No. 4, No. 5, No. 6 and No. vii, his Rückert songs and his song cycle Kindertotenlieder ("Songs on the Expiry of Children").[five]

Until 1901, Mahler's compositions had been heavily influenced by the High german folk-verse form collection Des Knaben Wunderhorn ("The Youth'due south Magic Horn"), which he had first encountered around 1887.[6] The music of Mahler'south many Wunderhorn settings is reflected in his Symphonies No. 2, No. three and No. 4, which all utilise vocal likewise every bit instrumental forces. From about 1901, however, Mahler's music underwent a change in character as he moved into the middle menstruation of his compositional life.[7] Hither, the more austere poems of Friedrich Rückert replace the Wunderhorn drove equally the chief influence; the songs are less folk-related, and no longer infiltrate the symphonies as extensively as before.[8] During this menstruation Symphonies No. v, No. six and No. 7 were written, all every bit purely instrumental works, portrayed by Mahler scholar Deryck Cooke as "more stern and forthright ..., more than tautly symphonic, with a new granite-like hardness of orchestration".[vii]

Mahler arrived at Maiernigg in June 1906 with the draft manuscript of his Seventh Symphony; he intended to spend fourth dimension revising the orchestration until an idea for a new piece of work should strike.[ix] The composer'due south wife Alma Mahler, in her memoirs, says that for a fortnight Mahler was "haunted by the spectre of failing inspiration";[10] Mahler's recollection, all the same, is that on the first day of the vacation he was seized by the creative spirit, and plunged immediately into composition of the work that would become his Eighth Symphony.[ix] [11]

Composition [edit]

Two notes in Mahler's handwriting dating from June 1906 show that early schemes for the work, which he may not at first have intended equally a fully choral symphony, were based on a iv-movement structure in which 2 "hymns" surround an instrumental cadre.[12] These outlines show that Mahler had fixed on the idea of opening with the Latin hymn, merely had not all the same settled on the precise course of the residuum. The first note is as follows:

- Hymn: Veni creator

- Scherzo

- Adagio: Caritas ("Christian love")

- Hymn: Die Geburt des Eros ("The birth of Eros")[12]

The second notation includes musical sketches for the Veni creator motion, and two bars in B pocket-size which are thought to relate to the Caritas. The four-movement plan is retained in a slightly unlike form, even so without specific indication of the extent of the choral element:

- Veni creator

- Caritas

- Weihnachtsspiele mit dem Kindlein ("Christmas games with the kid")

- Schöpfung durch Eros. Hymne ("Creation through Eros. Hymn")[12]

Mahler's composing hut at Maiernigg, where the Eighth Symphony was equanimous in summer 1906

From Mahler's after comments on the symphony's gestation, it is evident that the four-movement plan was relatively brusque-lived. He before long replaced the last three movements with a single section, essentially a dramatic cantata, based on the endmost scenes of Goethe'southward Faust, the depiction of an ideal of redemption through eternal womanhood (das Ewige-Weibliche).[13] Mahler had long nurtured an ambition to set the cease of the Faust epic to music, "and to set up it quite differently from other composers who take made information technology saccharine and feeble."[14] In comments recorded by his biographer Richard Specht, Mahler makes no mention of the original four-movement plans. He told Specht that having chanced on the Veni creator hymn, he had a sudden vision of the complete piece of work: "I saw the whole piece immediately before my optics, and only needed to write information technology downwards as though it were being dictated to me."[14]

The work was written at a frantic pace—"in record time", co-ordinate to the musicologist Henry-Louis de La Grange.[15] It was completed in all its essentials by mid-August, even though Mahler had to absent himself for a week to attend the Salzburg Festival.[xvi] [17] Mahler began composing the Veni creator hymn without waiting for the text to go far from Vienna. When information technology did, according to Alma Mahler, "the consummate text fitted the music exactly. Intuitively he had equanimous the music for the full strophes [verses]."[n 2] Although amendments and alterations were later on carried out to the score, in that location is very little manuscript evidence of the sweeping changes and rewriting that occurred with his earlier symphonies as they were prepared for performance.[18]

With its employ of song elements throughout, rather than in episodes at or near the cease, the work was the first completely choral symphony to be written.[nineteen] Mahler had no doubts most the ground-breaking nature of the symphony, calling information technology the grandest thing he had ever done, and maintaining that all his previous symphonies were merely preludes to it. "Try to imagine the whole universe kickoff to band and resound. There are no longer man voices, simply planets and suns revolving." It was his "gift to the nation ... a great joy-bringer."[20]

Reception and performance history [edit]

Premiere [edit]

A ticket for the premiere of the Eighth Symphony, Munich, 12 September 1910

The Neue Musik-Festhalle, venue of the premiere, at present part of the transportation centre of the Deutsches Museum

Mahler made arrangements with the impresario Emil Gutmann for the symphony to be premiered in Munich in the autumn of 1910. He soon regretted this involvement, writing of his fears that Gutmann would turn the performance into "a catastrophic Barnum and Bailey bear witness".[21] Preparations began early in the year, with the choice of choirs from the choral societies of Munich, Leipzig and Vienna. The Munich Zentral-Singschule provided 350 students for the children's choir. Meanwhile, Bruno Walter, Mahler's assistant at the Vienna Hofoper, was responsible for the recruitment and preparation of the 8 soloists. Through the spring and summer these forces prepared in their dwelling towns, before assembling in Munich early in September for three full days of final rehearsals under Mahler.[21] [1] His youthful assistant Otto Klemperer remarked after on the many small changes that Mahler made to the score during rehearsal: "He always wanted more clarity, more sound, more dynamic contrast. At ane bespeak during rehearsals he turned to us and said, 'If, later on my decease, something doesn't sound right, then change it. Y'all accept not only a correct but a duty to do and so.'"[22]

For the premiere, stock-still for 12 September, Gutmann had hired the newly built Neue Musik-Festhalle, in the Munich International Exhibition grounds near Theresienhöhe (now a branch of the Deutsches Museum). This vast hall had a chapters of 3,200; to assist ticket sales and raise publicity, Gutmann devised the nickname "Symphony of a One thousand", which has remained the symphony's popular subtitle despite Mahler's disapproval.[ane] [due north 3] Amid the many distinguished figures nowadays at the sold-out premiere were the composers Richard Strauss, Camille Saint-Saëns and Anton Webern; the writers Thomas Isle of man and Arthur Schnitzler; and the leading theatre director of the mean solar day, Max Reinhardt.[23] [1] Besides in the audience was the 28-yr-old British usher Leopold Stokowski, who six years later on would atomic number 82 the first United states performance of the symphony.[24] [25]

Up to this time, receptions of Mahler's new symphonies had commonly been disappointing.[23] Withal, the Munich premiere of the Eighth Symphony was an unqualified triumph;[26] as the final chords died away there was a short suspension before a huge outbreak of applause which lasted for 20 minutes.[23] Back at his hotel Mahler received a letter from Thomas Mann, which referred to the composer as "the human being who, as I believe, expresses the art of our time in its profoundest and most sacred grade".[27]

The symphony'south duration at its starting time performance was recorded past the critic-composer Julius Korngold as 85 minutes.[28] [n iv] This performance was the final fourth dimension that Mahler conducted a premiere of one of his ain works. 8 months after his Munich triumph, he died at the age of 50. His remaining works—Das Lied von der Erde ("The Song of the Earth"), his Symphony No. 9 and the unfinished Symphony No. 10—were all premiered after his death.[24]

Subsequent performances [edit]

On the day following the Munich premiere Mahler led the orchestra and choruses in a repeat performance.[33] During the next iii years, according to the calculations of Mahler's friend Guido Adler the Eighth Symphony received a further 20 performances across Europe.[34] These included the Dutch premiere, in Amsterdam under Willem Mengelberg on 12 March 1912,[33] and the starting time Prague performance, given on 20 March 1912 under Mahler's erstwhile Vienna Hofoper colleague, Alexander von Zemlinsky.[35] Vienna itself had to expect until 1918 before the symphony was heard there.[21]

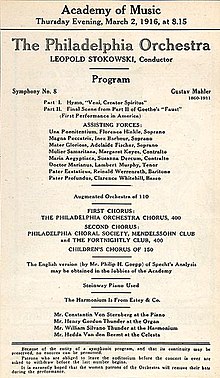

Program for the Us premiere of Mahler'southward 8th Symphony, Philadelphia, March 1916

In the U.Due south., Leopold Stokowski persuaded an initially reluctant board of the Philadelphia Orchestra to finance the American premiere, which took identify on ii March 1916.[36] [37] The occasion was a great success; the symphony was played several more than times in Philadelphia before the orchestra and choruses travelled to New York, for a serial of equally well-received performances at the Metropolitan Opera House.[25] [38]

At the Amsterdam Mahler Festival in May 1920, Mahler's completed symphonies and his major song cycles were presented over nine concerts given past the Concertgebouw Orchestra and choruses, under Mengelberg'south direction.[39] The music critic Samuel Langford, who attended the occasion, commented that "nosotros do non get out Amsterdam profoundly envying the nutrition of Mahler first and every other composer afterward, to which Mengelberg is training the music-lovers of that urban center."[40] The Austrian music historian Oscar Bie, while impressed with the festival as a whole, wrote subsequently that the Eighth was "stronger in effect than in significance, and purer in its voices than in emotion".[41] Langford had commented on the British "not being very eager well-nigh Mahler",[40] and the Eighth Symphony was non performed in U.k. until 15 April 1930, when Sir Henry Wood presented it with the BBC Symphony Orchestra. The work was played again 8 years afterwards by the same forces; among those present in the audience was the youthful composer Benjamin Britten. Impressed by the music, he nevertheless found the performance itself "execrable".[42]

The years after Earth War II saw a number of notable performances of the Eighth Symphony, including Sir Adrian Boult'southward circulate from the Regal Albert Hall on ten Feb 1948, the Japanese premiere under Kazuo Yamada in Tokyo in December 1949, and the Australian premiere nether Sir Eugene Goossens in 1951.[33] A Carnegie Hall performance under Stokowski in 1950 became the first complete recording of the symphony to be issued.[43] After 1950 the increasing numbers of performances and recordings of the work signified its growing popularity, but non all critics were won over. Theodor W. Adorno establish the piece weak, "a giant symbolic crush";[44] this almost affirmative piece of work of Mahler's is, in Adorno's view, his to the lowest degree successful, musically and artistically inferior to his other symphonies.[45] The composer-critic Robert Simpson, usually a champion of Mahler, referred to Part Ii as "an ocean of shameless kitsch."[44] Mahler biographer Jonathan Carr finds much of the symphony "bland", lacking the tension and resolution nowadays in the composer'south other symphonies.[44] Deryck Cooke, on the other mitt, compares Mahler'due south 8th to Beethoven's Choral (Ninth) Symphony. To Cooke, Mahler'southward is "the Choral Symphony of the twentieth century: like Beethoven's, but in a different fashion, information technology sets before u.s.a. an ideal [of redemption] which we are every bit however far from realising—even perchance moving away from—only which nosotros can hardly carelessness without perishing".[46]

In the tardily 20th century and into the 21st, the symphony was performed in all parts of the world. A succession of premieres in the Far East culminated in October 2002 in Beijing, when Long Yu led the Red china Philharmonic Orchestra in the start functioning of the work in the People's Republic of Communist china.[47] The Sydney Olympic Arts Festival in Baronial 2000 opened with a performance of the 8th by the Sydney Symphony Orchestra under its chief conductor Edo de Waart.[48] The popularity of the work, and its heroic scale, meant that it was often used equally a set piece on celebratory occasions; on 15 March 2008, Yoav Talmi led 200 instrumentalists and a choir of 800 in a performance in Quebec City, to mark the 400th anniversary of the city's foundation.[49] In London on 16 July 2010 the opening concert of the BBC Proms celebrated the 150th anniversary of Mahler'southward birth with a performance of the Eighth, with Jiří Bělohlávek conducting the BBC Symphony Orchestra.[50] This operation was its eighth in the history of the Proms.[51]

Analysis [edit]

Construction and class [edit]

The Eighth Symphony's two parts combine the sacred text of the 9th-century Latin hymn Veni creator spiritus with the secular text from the closing passages from Goethe'due south 19th-century dramatic poem Faust. Despite the axiomatic disparities inside this juxtaposition, the work every bit a whole expresses a single idea, that of redemption through the ability of beloved.[52] [53] The choice of these 2 texts was not arbitrary; Goethe, a poet whom Mahler revered, believed that Veni creator embodied aspects of his own philosophy, and had translated it into German in 1820.[32] Once inspired by the Veni creator thought, Mahler presently saw the Faust poem as an ideal counterpart to the Latin hymn.[54] The unity between the 2 parts of the symphony is established, musically, past the extent to which they share thematic material. In particular, the first notes of the Veni creator theme —

- Eastward ♭ → B ♭ → A ♭ :

— dominate the climaxes to each function;[52] at the symphony's culmination, Goethe's glorification of "Eternal Womanhood" is set in the form of a religious chorale.[46] It has been suggested that the Veni creator theme is based on Maos Tzur, a Jewish vocal sung at Hanukkah.[55]

In composing his score, Mahler temporarily abased the more progressive tonal elements which had appeared in his most recent works.[52] The symphony's key is, for Mahler, unusually stable; despite frequent diversions into other keys the music always returns to its primal E ♭ major.[46] This is the outset of his works in which familiar fingerprints—birdsong, military marches, Austrian dances—are almost entirely absent-minded.[52] Although the vast choral and orchestral forces employed suggest a work of awe-inspiring audio, according to critic Michael Kennedy "the predominant expression is not of torrents of sound but of the contrasts of subtle tone-colours and the luminous quality of the scoring".[19]

For Office I, almost modernistic commentators accept the sonata-form outline that was discerned by early analysts.[52] The structure of Function Two is more difficult to summarise, being an amalgam of many genres.[53] Analysts, including Specht, Cooke and Paul Bekker, have identified Adagio, Scherzo and Finale "movements" within the overall scheme of Office Ii, though others, including La Grange and Donald Mitchell, find petty to sustain this division.[56] The musicologist Ortrun Landmann has suggested that the formal scheme for Part II, after the orchestral introduction, is a sonata plan without the recapitulation, consisting of exposition, evolution and conclusion.[57]

Function I: Veni creator spiritus [edit]

Mahler'southward fair copy manuscript of the starting time folio of the Eighth Symphony

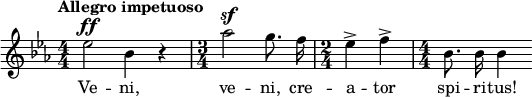

Mitchell describes Office I as resembling a giant motet, and argues that a key to its understanding is to read it every bit Mahler's endeavor to emulate the polyphony of Bach's great motets, specifically Singet dem Herrn ein neues Lied ("Sing to the Lord a new song").[53] The symphony begins with a unmarried tonic chord in E ♭ major, sounded on the organ, before the entry of the massed choirs in a fortissimo invocation: "Veni, veni creator spiritus".[n v]

The 3 note "creator" motif is immediately taken upwards by the trombones and and so the trumpets in a marching theme that volition be used as a unifying factor throughout the work.[46] [58]

![\relative c { \clef bass \key ees \major \numericTimeSignature \time 4/4 r4 ees->\ff bes-> aes'-> | \time 3/4 g8[ r16 f] ees4 | ees'~ | \time 4/4 ees }](https://upload.wikimedia.org/score/5/7/57qjz6m76uedbpgaohtj735m78h95q7/57qjz6m7.png)

After their first declamatory statement the two choirs appoint in a sung dialogue, which ends with a brusque transition to an extended lyrical passage, the plea "Imple superna gratia" ("Fill with divine grace").

![\relative c'' { \clef treble \key des \major \numericTimeSignature \time 4/4 aes2^\p bes4 aes8( bes) | c2( bes8[ aes)] des([ ees)] | f4. ees8 des2 } \addlyrics { Im -- ple su -- per -- na gra -- ti -- a, }](https://upload.wikimedia.org/score/c/f/cfnhuo9voboh11przn3c2n0sb2yq1mc/cfnhuo9v.png)

Here, what Kennedy calls "the unmistakable presence of twentieth-century Mahler" is felt as a solo soprano introduces a meditative theme.[31] She is soon joined by other solo voices as the new theme is explored before the choirs return exuberantly, in an A ♭ episode in which the soloists compete with the choral masses.[58]

In the next department, "Infirma nostri corporis / virtute firmans perpeti" ("Our weak frames fortify with thine eternal force"), the tonic fundamental of Eastward ♭ major returns with a variation of the opening theme. The section is interrupted by a short orchestral interlude in which the depression bells are sounded, adding a sombre touch to the music.[58] This new, less secure mood is carried through when "Infirma nostri corporis" resumes, this time without the choruses, in a subdued D minor echo of the initial invocation.[46]

At the terminate of this episode some other transition precedes the "unforgettable surge in East major",[58] in which the unabridged body of choral forces declaims "Accende lumen sensibus" ("Illuminate our senses").

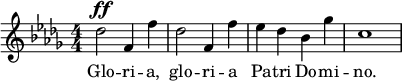

The first children'due south chorus follows, in a joyful mood, as the music gathers force and pace. This is a passage of great complexity, in the grade of a double fugue involving development of many of the preceding themes, with abiding changes to the cardinal signature.[46] [58] All forces combine over again in the recapitulation of the Veni creator section in shortened form. A quieter passage of recapitulation leads to an orchestral coda before the children's chorus announces the doxology Gloria sit Patri Domino ("Glory be to God the Father").

Thereafter the music moves swiftly and powerfully to its climax, in which an offstage brass ensemble bursts forth with the "Accende" theme while the primary orchestra and choruses stop on a triumphant rising scale.[46] [58]

Part II: Closing scene from Goethe'due south Faust [edit]

Mahler's manuscript score for the Chorus Mysticus, which provides the triumphant conclusion to the Eighth Symphony

The second part of the symphony follows the narrative of the final stages in Goethe'south poem—the journey of Faust's soul, rescued from the clutches of Mephistopheles, on to its final rise into sky. Landmann's proposed sonata construction for the move is based on a division, after an orchestral prelude, into five sections which he identifies musically every bit an exposition, three evolution episodes, and a finale.[59]

The long orchestral prelude (166 confined) is in E ♭ small-scale and, in the manner of an operatic overture, anticipates several of the themes which will be heard later in the movement. The exposition begins in near-silence; the scene depicted is that of a rocky, wooded mountainside, the domicile place of anchorites whose utterances are heard in an atmospheric chorus complete with whispers and echoes.[31] [46]

A solemn baritone solo, the voice of Pater Ecstaticus, ends warmly as the cardinal changes to the major when the trumpets audio the "Accende" theme from Part I. This is followed past a enervating and dramatic aria for bass, the vocalization of Pater Profundus, who ends his tortured meditation by asking for God'due south mercy on his thoughts and for enlightenment. The repeated chords in this section are reminiscent of Richard Wagner's Parsifal.[60] The mood lightens with the entry of the angels and blessed boys (women'south and children'southward choruses) bearing the soul of Faust; the music hither is perhaps a relic of the "Christmas Games" scherzo envisioned in the abortive iv-move draft plan.[31]

The atmosphere is festive, with triumphant shouts of "Jauchzet auf!" ("Rejoice!") earlier the exposition ends in a postlude which refers to the "Infirma nostri corporis" music from Part I.[threescore]

The kickoff stage of evolution begins equally a women's chorus of the younger angels invoke a "happy visitor of blessed children"[n 6] who must comport Faust'south soul heavenwards. The blessed boys receive the soul gladly; their voices are joined by Physician Marianus (tenor), who accompanies their chorus earlier breaking into a rapturous E major paean to the Mater Gloriosa, "Queen and ruler of the world!". As the aria ends, the male person voices in the chorus echo the soloist's words to an orchestral background of viola tremolos, in a passage described by La Grange as "emotionally irresistible".[sixty]

In the second part of the development, the entry of the Mater Gloriosa is signalled in Eastward major by a sustained harmonium chord, with harp arpeggios played over a pianissimo violin tune which La Grange labels the "love" theme.[threescore]

Thereafter the key changes oftentimes as a chorus of penitent women petition the Mater for a hearing; this is followed by the solo entreaties of Magna Peccatrix, Mulier Samaritana and Maria Aegyptiaca. In these arias the "beloved" theme is further explored, and the "scherzo" theme associated with the first advent of the angels returns. These 2 motifs predominate in the trio which follows, a request to the Mater on behalf of a 4th penitent, Faust's lover once known as Gretchen, who has come to make her plea for the soul of Faust.[60] After Gretchen's entreaty, a solo of "limpid dazzler" in Kennedy's words, an temper of hushed reverence descends.[31] The Mater Gloriosa then sings her merely ii lines, in the symphony's opening fundamental of E ♭ major, permitting Gretchen to lead the soul of Faust into heaven.[60]

The final development episode is a hymnlike tenor solo and chorus, in which Doctor Marianus calls on the penitents to "Gaze aloft".

A short orchestral passage follows, scored for an eccentric chamber group consisting of piccolo, flute, clarinet, harmonium, celesta, pianoforte, harps and a string quartet.[53] This acts equally a transition to the finale, the Chorus Mysticus, which begins in East ♭ major virtually imperceptibly—Mahler's annotation here is Wie ein Hauch, "like a breath".[60]

The sound rises in a gradual crescendo, as the solo voices alternately bring together or contrast with the chorus. As the climax approaches, many themes are reprised: the dearest theme, Gretchen'south song, the "Accende" from Part I. Finally, as the chorus concludes with "The eternal feminine draws usa on high", the off-stage contumely re-enters with a terminal salute on the Veni creator motif, to terminate the symphony with a triumphant flourish.[31] [threescore]

Instrumentation [edit]

Orchestra [edit]

A operation of Mahler's Eighth in Vienna in 2009 illustrates the scale of the instrumental and vocal forces employed.

The symphony is scored for a very large orchestra, in keeping with Mahler's conception of the work equally a "new symphonic universe", a synthesis of symphony, cantata, oratorio, motet, and lied in a combination of styles. La Grange comments: "To give expression to his cosmic vision, it was ... necessary to go beyond all previously known limits and dimensions."[fifteen] The orchestral forces required are, however, non as large as those deployed in Arnold Schoenberg's oratorio Gurre-Lieder, completed in 1911.[61] The orchestra consists of:

Mahler recommended that in very large halls, the outset player in each of the woodwind sections should exist doubled and that numbers in the strings should also be augmented. In addition, the piccolos, harps and mandolin, and the start offstage trumpet, should take 'several to the part' ['mehrfach besetzt'][61] [29]

Choral and vocal forces [edit]

- three soprano solos

- ii alto solos

- tenor solo

- baritone solo

- bass solo

- 2 SATB choirs

- children's choir

In Part Two the soloists are assigned to dramatic roles represented in Goethe's text, every bit illustrated in the post-obit table.[62]

| Voice type | Role | Premiere soloists, 12 September 1910[23] |

|---|---|---|

| First soprano | Magna Peccatrix (a sinful adult female) | Gertrude Förstel (Vienna Opera) |

| 2nd soprano | Una poenitentium (a penitent formerly known every bit Gretchen) | Martha Winternitz-Dorda (Hamburg Opera) |

| Third soprano | Mater Gloriosa (the Virgin Mary) | Emma Bellwidt (Frankfurt) |

| First alto | Mulier Samaritana (a Samaritan woman) | Ottilie Metzger (Hamburg Opera) |

| Second alto | Maria Aegyptiaca (Mary of Arab republic of egypt) | Anna Erler-Schnaudt (Munich) |

| Tenor | Dr. Marianus | Felix Senius (Berlin) |

| Baritone | Pater Ecstaticus | Nicola Geisse-Winkel (Wiesbaden Opera) |

| Bass | Pater Profundus | Richard Mayr (Vienna Opera) |

La Grange draws attention to the notably loftier tessitura for the sopranos, for soloists and for choral singers. He characterises the alto solos equally brief and unremarkable; yet, the tenor solo role in Part II is both extensive and enervating, requiring on several occasions to be heard over the choruses. The broad melodic leaps in the Pater Profundus role nowadays particular challenges to the bass soloist.[61]

Publication [edit]

Simply ane shorthand score of Symphony No. 8 is known to exist. Once the belongings of Alma Mahler, it is held by the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek in Munich.[52] In 1906 Mahler signed a contract with the Viennese publishing house Universal Edition (UE), which thus became the main publisher of all his works.[63] The full orchestral score of the 8th Symphony was published by UE in 1912.[64] A Russian version, published in Moscow past Izdatel'stvo Muzyka in 1976, was republished in the United States past Dover Publications in 1989, with an English text and notes.[65] The International Gustav Mahler Society, founded in 1955, has as its main objective the production of a complete disquisitional edition of all of Mahler's works. As of 2016 its disquisitional edition of the Eighth remains a project for the time to come.[66]

Recordings [edit]

Sir Adrian Boult'southward 1948 broadcast performance with the BBC Symphony Orchestra was recorded past the BBC, but non issued until 2009 when it was made available in MP3 form.[33] The showtime commercially issued recording of the complete symphony was performed by the Rotterdam Combo Orchestra conducted by Eduard Flipse. Information technology was recorded live by Philips at the 1954 Holland Festival.[67] [68] In 1962, the New York Philharmonic conducted by Leonard Bernstein made the first stereo recording of Function I for Columbia Records. This was followed in 1964 by the showtime stereo recording of the complete symphony, performed by the Utah Symphony conducted by Maurice Abravanel.[68]

Since the symphony was get-go recorded, at least 70 recordings have been made by many of the globe's leading orchestras and singers, more often than not during alive performances.[43]

Notes and references [edit]

Notes [edit]

- ^ Mahler had joined the Hofoper as a staff conductor in Apr 1897, and had succeeded Wilhelm Jahn as director in October of that year.[3]

- ^ Mitchell adds a caveat to this recollection: equally far as he had carried the limerick of the hymn at the fourth dimension when the text arrived. Given the scale of the move and its complexity, the suggestion that information technology was equanimous in its entirety in advance of the words is, in Mitchell's view, impossible to accept.[xviii]

- ^ It is not in fact certain that more than 1,000 performers participated in the Munich premiere. La Grange enumerates a chorus of 850 (including 350 children), 157 instrumentalists and the viii soloists, to give a total of ane,015. Nonetheless, Jonathan Carr suggests that there is evidence that not all the Viennese choristers reached the hall and the number of performers may therefore non take reached 1,000.[1]

- ^ The symphony's publishers, Universal Editions, give the duration as xc minutes,[29] as does Mahler's biographer Kurt Blaukopf.[xxx] Critic Michael Kennedy, however, estimates "roughly seventy-vii minutes".[31] A typical modern recording, the 1995 Deutsche Grammophon version under Claudio Abbado, plays for 81 minutes 20 seconds.[32]

- ^ English quotations from the Veni creator text are taken from the translation in Cooke, pp. 94–95

- ^ Quotations from the Faust text are based on the translation by David Luke, published in 1994 by Oxford University Printing and used in La Grange, pp. 896–904.

References [edit]

- ^ a b c d e Carr, pp. 206–207

- ^ See primarily Mahler'due south manuscript (Munich, Baayerische Staatsbibliothek, Mus. ms. 13719, OCLC 756354535), pp. 5 and 79 (of the digital object – the author uses the spelling "Theil") and the starting time edition (Wien, 1911), pp. 3 and 75; as well, the program for the American premiere showed below, §§§1.3.2 Subsequent performances, which lists "Part I" and "Part II".

- ^ Carr, p. 86

- ^ Blaukopf, p. 137

- ^ Blaukopf, pp. 158, 165, 203

- ^ Franklin, Peter (2007). "Mahler, Gustav". In Macy, Laura (ed.). Oxford Music Online . Retrieved 21 February 2010. (4. Prague 1885–86 and Leipzig 1886–88)

- ^ a b Cooke, p. 71

- ^ Mitchell, Vol. Ii p. 32

- ^ a b La Grange (2000), pp. 426–427

- ^ A. Mahler, p. 102

- ^ A. Mahler, p. 328

- ^ a b c La Grange (2000), p. 889

- ^ Kennedy, p. 77

- ^ a b Mitchell, Vol. 3 p. 519

- ^ a b La Grange (2000), p. 890

- ^ Kennedy, p. 149

- ^ La Grange (2000), pp. 432–447

- ^ a b Mitchell, Vol. Three pp. 523–525

- ^ a b Kennedy, p. 151

- ^ La Grange (2000), p. 926

- ^ a b c Blaukopf, pp. 229–232

- ^ Heyworth, p. 48

- ^ a b c d "Gustav Mahler: 8th Symphony: Function One". British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC). Retrieved 6 May 2016.

- ^ a b Gibbs, Christopher H. (2010). "Mahler Symphony No. eight, "Symphony of a Thousand"". Carnegie Hall. Archived from the original on 23 March 2016. Retrieved 6 May 2016.

- ^ a b Chasins, Abram (xviii April 1982). "Stokowski'due south Legend – Mickey Mouse to Mahler". The New York Times . Retrieved 9 May 2010.

- ^ "A New Choral Symphony". The Guardian. London. 15 September 1910. p. seven. Retrieved 21 May 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ A. Mahler, p. 342

- ^ La Grange (2000), pp. 913 and 918

- ^ a b "Gustav Mahler 8 Symphonie". Universal Edition. Retrieved xvi May 2010.

- ^ Blaukopf, p. 211

- ^ a b c d e f Kennedy, pp. 152–153

- ^ a b Mitchell: "The Creating of the Eighth" p. 11

- ^ a b c d Anderson, Colin (2009). "Sir Adrian Boult: Mahler'southward Symphony No. 8" (PDF). Music Preserved. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 June 2016. Retrieved viii May 2010.

- ^ Carr, p. 222

- ^ "Gustav Mahler: Works". Gustav Mahler 2010. 2010. Archived from the original on 21 March 2008. Retrieved 9 May 2010.

- ^ "Story of a Musical Masterpiece and of its Distinguished Author". The Philadelphia Inquirer. xx February 1916. p. xxx. Retrieved 21 May 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Offset American Production of Mahler's Eighth Symphony". The Philadelphia Inquirer. iii March 1916. p. ten. Retrieved 21 May 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "To Give Mahler's Choral Symphony". The New York Times. xxx January 1916. p. 25. Retrieved 21 May 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Blaukopf, p. 241

- ^ a b Langford, Samuel (1 July 1920). "The Mahler Festival in Amsterdam". The Musical Times. 61 (929): 448–450. doi:x.2307/908774. JSTOR 908774. (subscription required)

- ^ Painter, p. 358

- ^ Kennedy, Michael (13 Jan 2010). "Mahler's mass following". The Spectator. London. Retrieved 26 March 2010.

- ^ a b "Symphonie No 8 en Mi bémol majeur: Chronologie; Discographie: Commentaires". gustavmahler.net. Retrieved 24 Apr 2010.

- ^ a b c Carr, p. 186

- ^ La Grange (2000), p. 928

- ^ a b c d e f 1000 h Cooke, pp. 93–95

- ^ "Long Yu, Creative Director and Principal Conductor". The Chinese Embassy, Poland. 2004. Retrieved 9 May 2010.

- ^ "Olympic Arts Festival: Mahler's eighth Symphony". Australian Dissemination Corporation. 2007. Retrieved 9 May 2010.

- ^ "The Symphony of a Thousand in Québec Urban center". Quebec Symphony Orchestra (press release). xv March 2008. Archived from the original on 2016-06-10. Retrieved 6 May 2016.

- ^ "Proms 2010: What'due south on/Proms by week". Proms 2010. British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC). Archived from the original on 24 July 2010. Retrieved 11 August 2010.

- ^ "Performances of Symphony No. eight in E-apartment major Symphony of a Thousand". Proms Annal. British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC). Retrieved 1 March 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f La Grange (2000), pp. 905–907

- ^ a b c d Mitchell (1980), pp. 523–524

- ^ La Grange (2000), p. 891

- ^ Pickett, David (xiv December 2015). "Channukah in Summertime? (a annotation on Mahler's 8th Symphony)". wordpress.com.

- ^ La Grange (2000), p. 911

- ^ La Grange (2000), pp. 919–921

- ^ a b c d e f La Grange (2000), pp. 915–918

- ^ La Grange (2000), p. 896 and p. 912

- ^ a b c d e f g h La Grange (2000), pp. 922–925

- ^ a b c La Grange (2000), p. 910

- ^ Mitchell, Vol. Three pp. 552–567

- ^ La Grange (2000), pp. 501–502

- ^ Mitchell, Vol. III p. 592

- ^ Mahler, Gustav (1989). Symphony No. eight in full score. Mineola, New York: Dover Publications Inc. ISBN978-0-486-26022-8.

- ^ "The Complete Disquisitional Edition – Future Plans". The International Gustav Mahler Order. Retrieved sixteen May 2010.

- ^ Duggan, Tony. "The Mahler Symphonies: A Synoptic Survey by Tony Duggan — Symphony No. 8". MusicWeb International . Retrieved 29 December 2021.

The earliest commercial recording generally available came from a operation at Ahoy Hall in Rotterdam for the Holland Festival of 1955. It was conducted by a Mahler pioneer, Eduard Flipse, who came from the Dutch Mahler tradition. This recording was much honey of a previous generation of Mahlerites (not least for the unforgettable sound of the boys choruses—like a parliament of street urchins straight out of Fagin's kitchen) since information technology was, for some fourth dimension, the only recording you could get and even so has much to tell us.

- ^ a b "DISKS: VAST 8th Mahler's 'Symphony of a One thousand' Is At Last Recorded Stereophonically". New York Times. 3 May 1964. Retrieved 29 December 2021.

Sources [edit]

- Anderson, Colin (2009). "Sir Adrian Boult: Mahler's Symphony No. 8" (PDF). Music Preserved. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 June 2016. Retrieved eight May 2010.

- Blaukopf, Kurt (1974). Gustav Mahler. Harmondsworth, Uk: Futura Publications. ISBN978-0-86007-034-4.

- Carr, Jonathan (1998). Mahler: A Biography . Woodstock, New York: The Overlook Press. ISBN978-0-87951-802-8.

- Cooke, Deryck (1980). Gustav Mahler: An Introduction to his Music. London: Faber Music. ISBN978-0-571-10087-3.

- Franklin, Peter. "Mahler, Gustav". In Macy, Laura (ed.). Oxford Music Online . Retrieved 18 March 2010. (subscription required)

- Gibbs, Christopher H. (2010). "Mahler Symphony No. eight, "Symphony of a Thou"". Carnegie Hall. Archived from the original on 23 March 2016. Retrieved 6 May 2016.

- "Gustav Mahler 8 Symphonie". Universal Edition. Retrieved xvi May 2010.

- "Gustav Mahler: Eighth Symphony: Part One". British Dissemination Corporation (BBC). Retrieved vi May 2016.

- "Gustav Mahler: Works". Gustav Mahler 2010. Archived from the original on 21 March 2008. Retrieved 9 May 2010.

- Heyworth, Peter (1994). Otto Klemperer, His Life and Times, Volume 1 1885–1933. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN978-0-521-24293-6.

- Hoechst, Coit Roscoe (1916). Faust in Music. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh.

- Kennedy, Michael (1990). Mahler. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Printing. ISBN978-0-460-12598-seven.

- La Grange, Henry-Louis (2000). Gustav Mahler Volume 3: Vienna: Triumph and Disillusion (1904–1907). Oxford, United kingdom: Oxford University Press. ISBN978-0-nineteen-315160-4.

- Langford, Samuel (one July 1920). "The Mahler Festival in Amsterdam". The Musical Times. 61 (929): 448–450. doi:10.2307/908774. JSTOR 908774. (subscription required)

- "Long Yu, Creative Manager and Principal Conductor". The Chinese Embassy, Poland. 2004. Retrieved nine May 2010.

- Mahler, Alma (1968). Gustav Mahler: Memories and messages. London: John Murray.

- Mitchell, Donald (1975). Gustav Mahler Volume Two: The Wunderhorn Years: Chronicles and Commentaries. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN978-0-571-10674-5.

- Mitchell, Donald (1985). Gustav Mahler Book Three: Songs and Symphonies of Life and Death: Interpretations and Annotations. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN978-0-571-13634-six.

- Mitchell, Donald (1980). Sadie, Stanley (ed.). New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians Volume eleven. London: Macmillan. pp. 505–529. ISBN978-0-333-23111-1.

- Mitchell, Donald (1995). The Creating of the 8th (in booklet accompanying DGG recording 445 843-2). Hamburg: Deutsche Grammophon.

- Seckerson, Edward (April 2005). "Mahler: Symphony No. 8". Gramophone. London. p. 93. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

- Painter, Karen, ed. (2002). Mahler and His World. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN978-0-691-09244-7.

- "Symphonie No 8 en Mi bémol majeur: Chronologie; Discographie: Commentaires" (in French). gustavmahler.net. Retrieved 24 April 2010.

- Wildhagen, Christian (2000). Die Achte Symphonie von Gustav Mahler. Konzeption einer universalen Symphonik. Frankfurt am Main, Berlin, Bern, Bruxelles, New York, Oxford, Wien: Lang. ISBN978-3-631-35606-7.

External links [edit]

- Symphony No. 8 (Mahler, Gustav): Scores at the International Music Score Library Projection

- German and Latin texts, with English translation, taken from the Naxos 85505533-34 recording cond. Antoni Wit

DOWNLOAD HERE

Posted by: terrellthecumen.blogspot.com